I met Kimberlee two years ago, at Laity Lodge. We didn’t get much time to talk while we were there, and I came away from that retreat wishing I’d been able to carve out more time with Kimberlee. So, when I arrived home, I ordered a copy of her first book, The Circle of Seasons: Meeting God in the Church Year

I met Kimberlee two years ago, at Laity Lodge. We didn’t get much time to talk while we were there, and I came away from that retreat wishing I’d been able to carve out more time with Kimberlee. So, when I arrived home, I ordered a copy of her first book, The Circle of Seasons: Meeting God in the Church Year.* The description of this book on Amazon.com, ends like this: “In a word, The Circle of Seasons offers you structure–a simple and traditional way of building your life around your faith, rather than the other way around.” It’s true. The book is beautiful and, if you’re looking for some quiet encouragement on your journey with God, I highly recommend it.

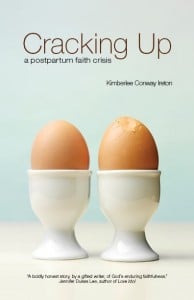

As you’ll see in this interview, Kimberlee’s experience with that book dovetails into the next phase of her spiritual journey—a journey which included pregnancy, the birth of twins, postpartum depression, and her slow return to solid ground. It’s this part of the journey Kimberlee shares in Cracking Up: A Postpartum Faith Crisis.*

You’ll enjoy the conversation here today. Kimberlee talks about the church calendar, depression, and faith. She also talks about the power of community, and gives insight into the writing life, handling rejection, and more. And, at the end of the interview, you’ll have the opportunity to receive a free copy of Kimberlee’s book.

:::

You begin the book like this: “The church year is the lens through which I see my life…” Can you tell us more about that? How did this particular perspective come to be, for you?

My first book is about the church year. Writing that book clarified and solidified a number of the disparate pieces of the church’s calendar that I’d been observing rather piecemeal over the years and helped me to see it more seamlessly, as an integrated whole. The process of writing that book and then living out the convictions it deepened in me has shaped my vision. What I meant when I wrote those words in Cracking Up is that I tend to look for connections between the church calendar and what is happening in my life. The church’s telling of time adds depth and dimension to my own small story.

Beneath this story of postpartum faith, there runs a river of the story of your previous book. As you tell it, that book was unsuccessful. Why was it important to you to weave these two stories together?

The story of my pregnancy and postpartum depression is inseparable from my vocation as a writer. It is the latter vocation that made me not want to have a third child—I thought I couldn’t mother three children well and also write as much as or in the ways that I wanted to. And I was right. I haven’t been able to. The year leading up to my pregnancy and the year that followed were years of intense professional pain—mounds of rejection letters, poor sales of my book, mounting fear that I had misheard my calling, or that economic and family pressure would make pursuing it unsustainable. The life I’d imagined for myself—as a writer and teller of stories—was beginning to implode. Throw a baby or two into that already tumultuous mix, and you get a big bang of fear.

From my vantage point, the process of writing a book is an incredibly intimate endeavor. It seems to be a mining of the writer’s heart and soul and then, bravely, you present this story to the world in all its glory. In what ways, if any, was the writing of this book similar to the experiences you tell of growing, carrying, and delivering life (twins!) into the world? How has it been different?

Wow, Deidra, what a great question. I think mostly what this book did for me was allow me to go back to those dark days from the other side and look at them again without the fear to swallow me whole. Writing this book didn’t feel as much like gestating as writing my first book did. I’m not sure why. Perhaps because it nearly wrote itself; all I did was show up, and out it poured. I still don’t know how I wrote it with four kids under the age of 9 hanging on my skirts. Actually, I do: For whatever reason, God wanted this book in the world, and it burned in me till I released it.

In the book, you tell the beautiful story of your faith community, and all the ways they surrounded you as you traveled through depression and despair. And of your husband, and your children, and your parents, and your sister, who walked the road with you, too. In many ways, they all seemed to rescue you, but (mostly) without crossing lines or boundaries. Is that an accurate assessment? Can you say more about the role of family and friends in our journeys of family, faith, and even failure?

I couldn’t have lived the months after my twins were born without my community. They were not and are not perfect people any more than I am, but when you’re in the depths of despair, you don’t need perfect; you just need company, someone to walk with you on the way—or clean your floors while you sleep for an hour. Except in a very few instances, I didn’t even mention in my book when boundaries got crossed.

Truth is, I don’t remember but a few of those instances; I was too deeply sunk in myself. The book is about that journey into the darkness of myself and back to the light of the living, and that is in some senses a journey we all take alone—no one can walk that road for us. But in another sense, I couldn’t have made the journey without the people who came alongside me to speak words of encouragement and provide tangible help: meals, house cleaning, babysitting.

And my husband in particular, who knew more than anyone else how deeply dark it was in my mind and how difficult, was a rock and a fortress.

I remember shortly after the twins were born, a friend was telling me about visiting her brother and his wife, who live in Chicago and are not church-goers, two weeks after the birth of their twins. When she showed up at their house, her brother was pacing the living room with one of the babies and muttering, “Two weeks. Two weeks! And only one f—ing lasagne!” I can’t even imagine that—we had food overflowing both our freezers and fresh meals delivered for months, and all I had to do was ask for some help (that’s the hard part, simply admitting that you need help), and voila, help arrived. I don’t know how people live without community. Rubbing up against other people can be super annoying—we’re all super annoying at times—but when life lands you flat on your back, you can’t do without all those annoying people coming around you to love on you and hold down the fort till you’re back on your feet.

Sorry! That’s a long answer to your question. I didn’t have time to write a short one.

Throughout the book, you have chapters—some longer than others—of Grace Notes. These lists of things for which you’re grateful often brought me to tears. They were simple, everyday, ordinary blessings. Can you say a few words about the sacredness of the simple, the everyday, and the ordinary?

Oh Deidra, what a gift to me! Thank you for saying they moved you to tears. That is going into my Blue Day File. I’ve been an avid journaler since I received my first journal for my 9th birthday (we’re coming up on 30 years of journaling here in a few months!), and one of the gifts of journaling is that it is a record of the simple, ordinary things of life, a way of remembering the sacredness, as you say, of the everyday.

Another gift of journaling is that if I know I’m going to be writing something down, I’m more likely to pay attention to what’s going on around me, so I have something to write about, which keeps me more grounded in the present moment than I am prone to be (I’m highly distractible, and live way too much in my head).

The Grace Notes were all drawn straight from my journal. Sometimes, in those months, I was so exhausted, all I could do in my journal was make a list of my blessings—I needed to make those lists, because life seemed so hard, and the deeper the darkness got, the more desperately I needed to hang on to the graces of daily life.

We live in a culture that is all about Big. But most of life isn’t lived large. It’s lived in the daily, moment-by-moment, small duties of our work and our relationships, so it’s there, in the ordinary normal, that we’re going to find grace and goodness and delight, if we find it at all. I choose to find it.

OK. You have four children, and the youngest are twins, right? What’s an ordinary day like for you?

Well, ordinarily (and I say that with hesitancy because ordinary is often disrupted when you’re dealing with little people who have their own agendas), ordinarily, we get up and have tea and eat breakfast and do morning chores and pray, often not in that order. Two mornings a week I take my twins to preschool and come home to do math and history and literature and Latin with my two older kids (yes, we homeschool; because I’m bat-crap crazy, happily so, but crazy nonetheless). When the twins aren’t in preschool, I read our various books to my older two while the twins play with Legos or Duplos on the floor. Then my older two do independent work at their desks for 30-60 minutes, while I read or play with the twins.

Well, ordinarily (and I say that with hesitancy because ordinary is often disrupted when you’re dealing with little people who have their own agendas), ordinarily, we get up and have tea and eat breakfast and do morning chores and pray, often not in that order. Two mornings a week I take my twins to preschool and come home to do math and history and literature and Latin with my two older kids (yes, we homeschool; because I’m bat-crap crazy, happily so, but crazy nonetheless). When the twins aren’t in preschool, I read our various books to my older two while the twins play with Legos or Duplos on the floor. Then my older two do independent work at their desks for 30-60 minutes, while I read or play with the twins.

Then we eat lunch. Usually after lunch the twins nap, Jack and Jane read quietly, and I either write or read or crash out with the twins; it depends on the day.

After quiet time, the kids play (or squabble) together, while I make dinner. Then it’s dinner, often with friends, which is a huge gift, these other adults in my children’s life, in my life. And then bedtime and the chaos that entails. Sometimes after the kids are in bed, I get to write or read a little more.

It sounds way more calm and organized than it actually is.

So, what’s your best advice for carving out time to write? When do you write, and where? What are your favorite writing tools (laptop, notebook, pen, tablet, etc.)?

I don’t know that I have great advice for carving out time to write. When I was working on my books, I hired babysitters to watch my kids so I could write. I’ve left my kids with my husband on Saturdays for months on end so I could write. I’ve stayed up way too late at night to write. I’ve squeezed writing in during their naps.

As for tools, I use a laptop for most of my work. But a pen and paper are also a significant part of my writing process. I hand write in my journal. When I write poetry, I always write it by hand first (probably because poems don’t come to me when I’m at a computer but when I’m out and about). When I’m stuck on a piece and can’t make headway, I go back to pen and paper. It’s how I learned to write, and even though I’m quite comfortable composing on a keyboard, I think hand-writing is still my native language.

What is your favorite book about writing? Why do you like it?

Oh mercy. Do I have to pick one? It would probably be Walking on Water*, by Madeleine L’Engle. I keep it on my writing desk, right beside my dictionary and my thesaurus and my vocabulary notebook (where I collect words). I like it because it was the first L’Engle book I read. (I was 20. I know. My childhood was rather deprived in terms of excellent books, though we did read The Wind in the Willows three times as a family, and A Secret Garden was my favorite book, until I read Anne of Green Gables at 14. But I didn’t read A Wrinkle in Time till I was 21.) But where was I? Oh, yes, reading Walking on Water at 20 when I was studying in England, the homeland of my spirit, gave me permission to own the dabbling I’d done in words all my life and call it art. It gave me a vision of Christian writing that wasn’t confined to Christian topics. It helped me see more deeply that all truth is God’s truth, and that the only way my writing would be Christian is if I were Christian. I believe that now with my whole soul, and it both encourages and frightens me.

And what about rejection? What would you say about that?

Get used to it? I’m not sure what else to say. It sucks. It hurts. It’s part of being a writer (or an actor or a singer or any number of creative careers). Don’t let it stop you. And don’t, whatever you do, let it define you. Don’t go all incurvatus in se (turned inward) in the face of it. Learn what you can from it, but ultimately it’s not the rejection that defines you as a writer (unless you let it—don’t let it!); it’s how you respond to the rejection. Are you going to curl up in a ball or are you going to keep your head raised and your arms wide to embrace whatever comes next? It’s the hardest part of being not just a writer but a human being: not letting our hurts define us, not letting them turn us in on ourselves. Jesus’ posture on the cross is one of embrace, arms wide to hug the world, and it’s the posture we’re called to as His followers, even (especially?) in the face of rejection.

What one thing do you want readers to know?

For this book, the one thing I wanted readers to know is that they’re not alone. If my book can provide solace and a sense of solidarity—a sense that oh thank God I’m not the only one—that would be enough. If it helped someone to see—really see—that God is present in the darkest of places and holding them, that would be—I don’t really have words for how great a gift that would be. And I am rarely wordless.

Kimberlee has graciously offered to give away a copy of Cracking Up to one of you! To be entered to win, please answer this question in the comments: How have you been rescued by the beauty of community?

Update: Mary Bonner is the winner of Kimberlee’s book! Congratulations, Mary!

Kimberlee Conway Ireton is the author of The Circle of Seasons: Meeting God in the Church Year and the recently released memoir, Cracking Up: A Postpartum Faith Crisis You can also find her words at Godspace, A Deeper Story, and Tweetspeak Poetry as well as on her own blog.

Kimberlee Conway Ireton is the author of The Circle of Seasons: Meeting God in the Church Year and the recently released memoir, Cracking Up: A Postpartum Faith Crisis You can also find her words at Godspace, A Deeper Story, and Tweetspeak Poetry as well as on her own blog.

A wannabe connoisseur of tea and an avid reader, Kimberlee lives in Seattle with her husband, four kids, two cats, and more books than she can count.

*affiliate links